All about Concurrency in Swift - Part 1: The Present

Posted on May 7, 2017 中文版 | 한국어

Update 10/17: Updated for Swift 4

Update: The second part of this series is now available: All About concurrency in Swift - Part 2: The Future.

The current release of the Swift language doesn’t include yet any native concurrency functionality like other modern languages such as Go or Rust do.

If you plan to perform tasks concurrently and when you’ll need to deal with the resulting race conditions, your only option is to use external libraries like libDispatch or the synchronization primitives offered by Foundation or the OS.

In the first part of this series, we’ll take a look at what we have at our disposal with Swift 3, covering everything from Foundation locks, threads and timers to the language guarantees and the recently improved Grand Central Dispatch and Operation Queues.

Some basic concurrency theory and a few common concurrency pattern will also be described.

Even if they are available on every platform where Swift is available, the functions and primitives from the pthread library will not be discussed here, since for all of them, higher level alternatives exist. The NSTimer class will also not be described here, take a look here for info on how to use it with Swift 3.

As has already been announced multiple times, one of the major releases after Swift 4.0 (not necessarily Swift 5) will expand the language to better define the memory model and include new native concurrency features that will allow to handle concurrency, and likely parallelism, without external libraries, defining a swifty idiomatic approach to concurrency.

This will be the topic of the next article in this series, where we’ll discuss a few alternative approaches and paradigms implemented by other languages, how they could be implemented in Swift and we’ll analyze a few open-source implementations that are already available today and that allow to use the Actors paradigm, Go’s CSP channels, Software Transactional Memory and more with the current release of Swift.

This second article will be completely speculative and its main goal will be to give you an introduction to these subjects so that you’ll be able to participate to the, likely heated, discussions that will define how concurrency will be handled in the future releases of Swift.

The playgrounds for this and other articles are available from GitHub or Zipped.

Contents

- Multithreading and Concurrency Primer

- Language Guarantees

- Threads

- Synchronization Primitives

- GCD: Grand Central Dispatch

- Operations and OperationQueues

- Closing Thoughts

Multithreading and Concurrency Primer

Nowadays, regardless of what kind of application you are building, sooner or later you’ll have to consider the fact that your application will be running in an environment with multiple threads of execution.

Computing platforms with more than one processors or processors with more than one hardware execution core have been around for a few decades and concept like thread and process are even older than that.

Operating systems have been exposing these capabilities to user programs in various ways and every modern framework or application will likely implement a few well known design pattern involving multiple threads to improve flexibility and performance.

Before we start to delve into the specifics of how to deal with concurrency with Swift, let me explain briefly a few basic concepts that you need to know before starting to consider if you should use Dispatch Queues or Operation Queues.

First of all, you could ask, even if Apple’s platform and frameworks use threads, why should you introduce them in your applications?

There are a few common circumstances that make the use of multiple threads a no-brainer:

-

Task groups separation: Threads can be used to modularize your application from the point of view of execution flow, different threads can be used to execute in a predictable manner a group of task of the same type, isolating them from the execution flow of other parts of your program, making it easier to reason about the current state of your application.

-

Parallelize data-independent computations: Multiple software threads, backed by hardware threads or not(see next point), can be used to parallelize multiple copies of the same task operating on a subset of an original input data structure.

-

Clean way to wait for conditions or I/O: When using blocking I/O or when performing other kinds of blocking operations, background threads can be used to cleanly wait for the completion of these operations. The use of threads can improve the overall design of your application and make handling blocking calls trivial.

But when multiple threads are executing your application code, a few assumptions that made sense when looking at your code from the point of view of a single thread cease to be valid.

In an ideal world where each thread of execution behave independently and there is no sharing of data, concurrent programming is actually not much more complex that writing code that will be executed by a single thread. But if, as often happens, you plan to have multiple threads operating on the same data, you’ll need a way to regulate access to those data structures and to guarantee that every operation on that data completes as expected without unwanted interaction with operations from other threads.

Concurrent programming requires additional guarantees from the language and the operating system, that need to explicitly state how variables (or more generically “resources”) will behave when multiple threads try to alter their value accessing them at the same time.

The language needs to define a Memory Model, a set of rules that explicitly states how some basic statements will behave in presence of concurrent threads, defining how memory can be shared and which kind of memory accesses are valid.

Thanks to this, the user will have a language that behave predictably in the presence of threads and we’ll know that the compiler will only perform optimizations that respect what has been defined in the memory model.

Defining a memory model is a delicate step in the evolution of a language, since a model too strict could limit how the compiler will be allowed to evolve. New clever optimizations could be invalid as a consequence of past decisions on the memory model.

The memory model defines for example:

-

Which language statements can be considered atomic and which are not, operations that can be executed only as a whole where no thread can see partial results. It’s for example essential to know if variables are initialized atomically or not.

-

How shared variables are handled by threads, if they are cached by default or not and if it would be possible to influence the caching behaviour with specific language modifiers.

-

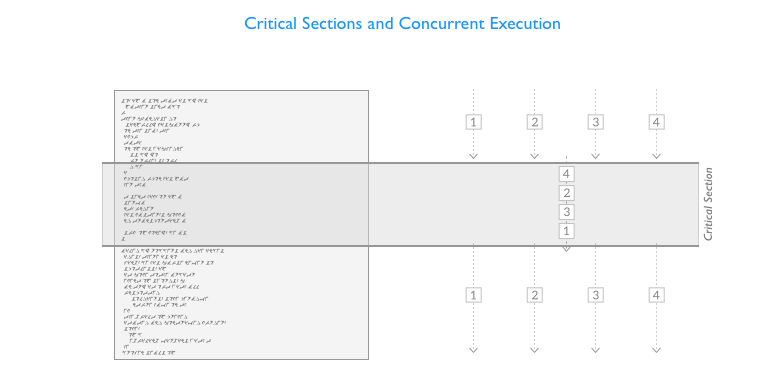

Concurrency operators that are used to mark and to regulate access to critical sections, sections of code that operate on shared resources, allowing for example only one thread to follow a specific code path at a time.

Now let’s go back to discussing the use of concurrency in your programs.

To handle concurrency correctly, you’ll have to identify the critical sections in your program and use concurrency primitives or concurrency-aware data structure to regulate access to data shared among different threads.

Imposing access rules to these sections of code or data structures open the way to another set of problems, that derive from the fact that while the desired outcome is that every thread gets to be executed and has a chance to modify the shared data, under some circumstances some of them could not execute at all or the data could be altered in unexpected and unpredictable ways.

You’ll face an additional set of challenges and you’ll have to work around some common problems:

-

Race conditions: With multiple threads operating on the same data, for example reading and writing it concurrently, the outcome of the execution of a series of operations could become unpredictable and dependent on the order of execution of the threads.

-

Resources contention: Multiple threads, that could be performing different tasks, trying to access the same resources will increase the amount of time needed to obtain the required resources safely. These delays needed to acquire the resources you need could lead to unexpected behaviour or could require that you structure your program to regulate access to these resources.

-

Deadlocks: Multiple threads waiting for each other to release the resources/locks they need, forever, blocking the execution of that group of threads.

-

Starvation: A thread could never be able to acquire the resource, or a set of resources in a specific order, it needs for various reasons and keep trying forever unsuccessfully to acquire them.

-

Priority Inversion: A thread with lower priority could keep acquiring resources needed for a thread with higher priority effectively inverting the priority assigned by the system.

-

Non-determinism and Fairness: We can’t make assumptions on when and in what order a thread will be able to acquire a shared resource, this delay cannot be determined a priori and is heavily influenced by the amount of contention. A thread could even never be able to acquire a resource. But concurrency primitives used to guard a critical section can also be built to be fair or to support fairness, guaranteeing access to the critical section to all the threads that are waiting, also respecting the request order.

Language Guarantees

Even if at the moment the Swift language itself doesn’t have features related to concurrency, it still offers some guarantees related to how properties are accessed.

Global variables for example are initialized atomically, we will never need to handle manually the case in which multiple threads try to initialize the same global variable concurrently or worry that someone could see a partially initialized variable while initialization is still ongoing.

We’ll discuss again this behaviour when talking about implementing singletons below.

But it’s important to remember that lazy properties initialization is instead not performed atomically, and the language for now does not provide annotations or modifiers to change this behaviour.

Access to class properties is again not atomic, and if you need to make it so, you’ll have to implement exclusive access manually using locks or similar mechanisms.

Threads

Foundation offers a Thread class, internally based on pthread, that can be used to create new threads and execute closures.

Threads can be created using the method detachNewThreadSelector:toTarget:withObject: of the Thread class or we can create a new thread declaring a custom Thread class and then overriding the main() method:

class MyThread : Thread {

override func main(){

print("Thread started, sleep for 2 seconds...")

Thread.sleep(forTimeInterval:2)

print("Done sleeping, exiting thread")

}

}

But since iOS 10 and macOS Sierra, it’s finally possible on all platforms to just create a new thread using the initializer that allows to specify the closure that the thread will execute. All the example in this article will still extend the base Thread class though, so that you don’t have to worry about having the right OS to try them out.

var t = Thread {

print("Started!")

}

t.stackSize = 1024 * 16

t.start() //Time needed to spawn a thread around 100us

Once we have a thread instance we need to manually start it. As an optional step, we can also choose a custom stack size for this new thread.

Threads can be stopped abruptly calling exit() but that’s never recommended since it doesn’t give you the opportunity to cleanly end the current task, most of the times you’ll implement the stopping logic yourself if you need it or just use the cancel() method and check the isCancelled property inside your main closure to know if the thread is required to stop the current job before its natural end.

Synchronization Primitives

When we have different threads that want to mutate shared data, is essential to handle synchronization of those threads in some way to prevent data corruption and non-deterministic behavior.

The basic facilities usually used to synchronize threads are locks, semaphores and monitors.

Foundation provides all of them.

As you’ll see momentarily, the classes (yes, all of them are reference types) implementing these constructs have not lost the NS prefix in Swift 3, but could in one of the next releases of Swift.

NSLock

NSLock is the basic type of lock that Foundation offers.

When a thread tries to lock this object two things can happen, the thread will acquire the lock and proceed if it hasn’t already been acquired by a previous thread or alternatively the thread will wait, blocking its execution, until the owner of the lock unlocks it. In other words, locks are object that can be acquired (or locked) only by one thread at a time and this make them perfect to monitor access to critical sections.

NSLock and the other Foundation’s locks are unfair, meaning that when a series of threads is waiting to acquire a lock, they will not acquire it in the same order in which they originally tried to lock it.

You can’t make assumption on the execution order, and in cases of high thread contention, when a lot of threads are trying to acquire the resource, some of your threads may be subject to starvation and never be able to acquire the lock they are waiting for (or not able to acquire it in a timely fashion).

The time needed to acquire a lock, without contention, is measurable in 100s of nanoseconds, but that time grows rapidly when more than one thread tries to acquire the locked resource. So, from a performance point of view, locks are usually not the best solution to handle resource allocation.

Let’s see an example with two threads and remember that since the order in which the lock will be acquired is not deterministic, it could happen that T1 acquires the Lock two times in a row (but that wouldn’t be the norm).

let lock = NSLock()

class LThread : Thread {

var id:Int = 0

convenience init(id:Int){

self.init()

self.id = id

}

override func main(){

lock.lock()

print(String(id)+" acquired lock.")

lock.unlock()

if lock.try() {

print(String(id)+" acquired lock again.")

lock.unlock()

}else{ // If already locked move along.

print(String(id)+" couldn't acquire lock.")

}

print(String(id)+" exiting.")

}

}

var t1 = LThread(id:1)

var t2 = LThread(id:2)

t1.start()

t2.start()

Let me just add a word of warning for when you’ll decide to use locks. Since it’s likely that sooner or later you’ll have to debug concurrency issues, always try to circumscribe your use of locks inside the bounds of some sort of data structure and try not to refer directly to a single lock object in multiple places in your code base.

Checking the status of a synchronized data structure with few entry points while debugging a concurrency problem is way more pleasant than having to keep track of which part of your code is holding a lock and having to remember the local status of multiple functions. Go the extra mile and structure well your concurrent code.

NSRecursiveLock

Recursive locks can be acquired multiple times from the thread that already holds that lock, useful in recursive function or when calling multiple functions that check the same lock in sequence. This would not work with basic NSLocks.

let rlock = NSRecursiveLock()

class RThread : Thread {

override func main(){

rlock.lock()

print("Thread acquired lock")

callMe()

rlock.unlock()

print("Exiting main")

}

func callMe(){

rlock.lock()

print("Thread acquired lock")

rlock.unlock()

print("Exiting callMe")

}

}

var tr = RThread()

tr.start()

NSConditionLock

Condition locks provides additional sub-locks that can be locked/unlocked independently from each other to support more complex locking setups (e.g. consumer-producer scenarios).

A global lock (that locks regardless of a specific condition) is also available and behaves like a classic NSLock.

Let’s see a simple example with a lock that guards a shared integer, that a consumer prints and a producer updates every time it has been shown on screen.

let NO_DATA = 1

let GOT_DATA = 2

let clock = NSConditionLock(condition: NO_DATA)

var SharedInt = 0

class ProducerThread : Thread {

override func main(){

for i in 0..<5 {

clock.lock(whenCondition: NO_DATA) //Acquire the lock when NO_DATA

//If we don't have to wait for consumers we could have just done clock.lock()

SharedInt = i

clock.unlock(withCondition: GOT_DATA) //Unlock and set as GOT_DATA

}

}

}

class ConsumerThread : Thread {

override func main(){

for i in 0..<5 {

clock.lock(whenCondition: GOT_DATA) //Acquire the lock when GOT_DATA

print(i)

clock.unlock(withCondition: NO_DATA) //Unlock and set as NO_DATA

}

}

}

let pt = ProducerThread()

let ct = ConsumerThread()

ct.start()

pt.start()

When creating the lock, we need to specify the starting condition, represented by an integer.

The lock(whenCondition:) method will acquire the lock when the condition is met or will wait until another thread sets that value when releasing the lock using unlock(withCondition:).

A small improvement over basic locks that allows us to model slightly more complex scenarios.

NSCondition

Not to be confused with Condition Locks, a condition provide a clean way to wait for a condition to occur.

When a thread that has acquired a lock verifies that an additional condition it needs (some resource it needs, another object being in a particular state, etc…) to perform its work is not met, it needs a way to be put on hold and continue its work once that condition is met.

This could be implemented by continuously or periodically checking for that condition (busy waiting) but doing so, what would happen to the locks the thread holds? Should we keep them while we wait or release them hoping that we’ll be able to acquire them again when the condition is met?

Conditions provide a clean solution to this problem, once acquired a thread can be put on a waiting list for that condition and is woken up once another thread signals that the condition has been met.

Let’s see an example:

let cond = NSCondition()

var available = false

var SharedString = ""

class WriterThread : Thread {

override func main(){

for _ in 0..<5 {

cond.lock()

SharedString = "😅"

available = true

cond.signal() // Notify and wake up the waiting thread/s

cond.unlock()

}

}

}

class PrinterThread : Thread {

override func main(){

for _ in 0..<5 { //Just do it 5 times

cond.lock()

while(!available){ //Protect from spurious signals

cond.wait()

}

print(SharedString)

SharedString = ""

available = false

cond.unlock()

}

}

}

let writet = WriterThread()

let printt = PrinterThread()

printt.start()

writet.start()

NSDistributedLock

Distributed locks are quite different from what we’ve seen until now and I don’t expect that you’ll need them frequently.

They are made to be shared between multiple applications and are backed by an entry on the file system (for example a simple file). The file system will obviously need to be accessible by all the applications that need to acquire it.

This kind of lock is acquired using the try() method, a non blocking method that returns right away with a boolean indicating if the lock was acquired or not. Acquiring a lock will usually require more than one try, to be performed manually and with a proper delay between successive attempts.

Distributed locks are released as usual using the unlock() method.

Let’s see a basic example:

var dlock = NSDistributedLock(path: "/tmp/MYAPP.lock")

if let dlock = dlock {

var acquired = false

while(!acquired){

print("Trying to acquire the lock...")

usleep(1000)

acquired = dlock.try()

}

// Do something...

dlock.unlock()

}

OSAtomic Where Art Thou?

Atomic operations like those that were provided by OSAtomic are simple operations that allow to set, get or compare-and-set variables without using the classic locking logic because they leverage specific CPU functionalities (sometimes native atomic instructions) and that provide way better performance than the locks described previously.

It goes without saying that they are extremely useful to build concurrent data structures, since the overhead needed to handle concurrency is reduced to a minimum.

OSAtomic has been deprecated since macOS 10.12 and was never available on Linux, but a few open source project like this with its useful Swift extensions or this provide similar functionalities. Also, check out the recently released AtomicKit.

On Synchronized Blocks

In Swift you can’t create a @synchronized block out of the box as you would do in Objective-C, since there is no equivalent keyword available.

On Darwin, with a bit of code you could roll out something similar to the original implementation of @synchronized using objc_sync_enter(OBJ) and objc_sync_exit(OBJ) to enter and exist an @objc object monitor like @synchronized does under the hood, but it’s not recommended, it’s better to simply use a lock if you need something like that, more versatile.

And as we’ll see when describing Dispatch Queues, we can use queues to replicate this functionality with even less code performing a synchronous call on a serial queue:

serialQueue.sync {

// Only a thread at a time!

v += 1

print("Current value \(v)")

}

The playgrounds for this and other articles are available from GitHub or Zipped.

GCD: Grand Central Dispatch

For those that are not already familiar with this API, the Grand Central Dispatch (GCD) is a queue based API that allows to execute closures on workers pools.

In other words, closures containing a job that need to be executed can be added to a queue that will execute them using a series of threads either sequentially or in parallel depending on the queue’s configuration options. But regardless of the type of queue, jobs will always be started following the First-in First-out order, meaning that the jobs will always be started respecting the insertion order. The completion order will depend on the duration of each job.

This is a common pattern that can be found in nearly every relatively modern language runtime that handles concurrency. A thread pool is way more easy to manage, inspect and control than a series of free and unconnected threads.

The GCD API had a few changes in Swift 3, SE-0088 modernized its design and made it more object oriented.

Dispatch Queues

The GCD allows the creation of custom queues but also provide access to some predefined system queues.

To create a basic serial queue, a queue that will execute your closures sequentially, you just need to provide a string label that will identify it and it’s usually recommended to use a reverse order domain name prefix to simplify tracking back the owner of the queue in stack traces.

let serialQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.uraimo.Serial1") //attributes: .serial

let concurrentQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.uraimo.Concurrent1", attributes: .concurrent)

The second queue we created is concurrent, meaning that the queue will use all the available threads in its underlying thread pool when executing the jobs it contains. Order of execution is unpredictable in this case, don’t assume that the completion order of your closures will be in any way related to the insertion order.

The default queues can be retrieved from the DispatchQueue object:

let mainQueue = DispatchQueue.main

let globalDefault = DispatchQueue.global()

The main queue is the sequential main queue that handles the main event loop for graphical applications on either iOS or macOS, responding to events and updating the user interface. As we know, every alteration to the user interface should be performed on this queue and every long operation performed on this thread will render the user interface less responsive.

The runtime also provides access to other global queues with different priorities that can be identified by their Quality of Service (Qos) parameter.

The different levels of priority are declared in the DispatchQoS class, from higher to lower:

- .userInteractive

- .userInitiated

- .default

- .utility

- .background

- .unspecified

It’s important to note that on mobile devices that provide a low power mode, background queues will be suspended when the battery is running low.

To retrieve a specific default global queue, use the global(qos:) getter specifying the desired priority:

let backgroundQueue = DispatchQueue.global(qos: .background)

The same priority specifier can be used with or without other attributes also when creating custom queue:

let serialQueueHighPriority = DispatchQueue(label: "com.uraimo.SerialH", qos: .userInteractive)

Using Queues

Jobs, in the form of closures, can be submitted to a queue in two ways: synchronously using the sync method or asynchronously with the async method.

When using the former, the sync call will be blocking, in other words, the call to the sync method will complete when its closure will complete (useful when you need to wait for the closure to end, but there are better approaches), whereas the former will add the closure to the queue and complete, scheduling the closure for deferred execution and allowing the current function to continue.

Let’s see a quick example:

globalDefault.async {

print("Async on MainQ, first?")

}

globalDefault.sync {

print("Sync in MainQ, second?")

}

Multiple dispatch calls can be nested, for example when after some background, low priority, operation executed on a queue of our choosing, we need to update the user interface form the main queue.

DispatchQueue.global(qos: .background).async {

// Some background work here

DispatchQueue.main.async {

// It's time to update the UI

print("UI updated on main queue")

}

}

Closures can also be executed after a specific delay, Swift 3 finally allows to specify in a more comfortable way the desired time interval with the utility enum DispatchTimeInterval that allows to compose intervals using these four time units: .seconds(Int), .milliseconds(Int), .microseconds(Int) and .nanoseconds(Int).

To schedule a closure for future execution use the asyncAfter(deadline:execute:) method with a time interval:

globalDefault.asyncAfter(deadline: .now() + .seconds(5)) {

print("After 5 seconds")

}

If you need to execute multiple iteration of the same closure concurrently (like you were used to to with the dispatch_apply) you can use the concurrentPerform(iterations:execute:) method, but beware, these closure will be executed concurrently if possible in the context of the current queue, so remember to always enclose a call to this method in a sync or async call running on a queue that support concurrency.

globalDefault.sync {

DispatchQueue.concurrentPerform(iterations: 5) {

print("\($0) times")

}

}

While normally a queue is ready to process its closures upon creation, it can be configured to start in an idle state and to start processing jobs only when manually enabled.

let inactiveQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.uraimo.inactiveQueue", attributes: [.concurrent, .initiallyInactive])

inactiveQueue.async {

print("Done!")

}

print("Not yet...")

inactiveQueue.activate()

print("Gone!")

This is the first time we need to specify more than one attribute, but as you can see, you can just add multiple attributes with an array if needed.

Execution of jobs can also be suspended or resumed temporarily with methods inherited from DispatchObject:

inactiveQueue.suspend()

inactiveQueue.resume()

A setTarget(queue:) method that is to be used only to configure the priority of inactive queues (using it on active queues will result in a crash) is also available. The result of calling this method is that the priority of the queue is set to the same priority of the queue given as parameter.

Barriers

Let’s say you added a series of closures to a specific queue (with different durations) but you now want to execute a job only after all the previous asynchronous task are completed. You can use barriers to do it.

Let’s add 20 tasks (that will sleep for a timeout of 1 second) to the concurrent queue we created previously and use a barrier to print something once the other jobs complete, we’ll do this specifying a flag DispatchWorkItemFlags.barrier in our final async call:

let concurrentQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.uraimo.Concurrent", attributes: .concurrent)

concurrentQueue.async {

DispatchQueue.concurrentPerform(iterations: 5) { (id:Int) in

sleep(1)

print("Async on concurrentQueue, 5 times: "+String(id))

}

}

concurrentQueue.async (flags: .barrier) {

print("All 5 concurrent tasks completed")

}

The 20 tasks will be executed in parallel without a specific order by the concurrent queue and you’ll see those messages appearing in groups of a size equal to the number of execution cores of your Mac, but the final call will always be executed last.

Barriers are a way to impose ordering on concurrent queues that normally don’t execute the registered tasks in a repeatable order.

As Arthur Hammer notes, it’s important to remember that dispatch barriers have no effect on serial queues and on any of the global concurrent queues. You’ll need to define a new custom concurrent queue if you plan to use them.

Singletons and Dispatch_once

As you could have already noticed, in Swift 3 there is no equivalent of dispatch_once, a function used most of the times to build thread-safe singletons.

Luckily, Swift guarantees that global variables are initialized atomically and if you consider that constants can’t change their value after initialization, these two properties make global constants a great candidate to easily implement singletons:

final class Singleton {

public static let sharedInstance: Singleton = Singleton()

private init() { }

...

}

We’ll declare the class as final to deny the ability to subclass and we’ll make the designated initializer private, so that it will not be possible to manually create additional instances of this object. A public static constant will be the only entry point of the singleton and will be used to retrieve the single, shared, instance.

The same behaviour can be used to define blocks of code that will be executed only once:

func runMe() {

struct Inner {

static let i: () = {

print("Once!")

}()

}

Inner.i

}

runMe()

runMe() // Constant already initialized

runMe() // Constant already initialized

It’s not really pretty to look at but it works, and it could be an acceptable implementation if it’s just a one time thing™.

But if we need to replicate exactly the functionality and API of dispatch_once we need to implement it from scratch, as described in the synchronized blocks section with an extension:

import Foundation

public extension DispatchQueue {

private static var onceTokens = [Int]()

private static var internalQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "dispatchqueue.once")

public class func once(token: Int, closure: ()->Void) {

internalQueue.sync {

if onceTokens.contains(token) {

return

}else{

onceTokens.append(token)

}

closure()

}

}

}

let t = 1

DispatchQueue.once(token: t) {

print("only once!")

}

DispatchQueue.once(token: t) {

print("Two times!?")

}

DispatchQueue.once(token: t) {

print("Three times!!?")

}

As expected, only the first of the three closures will be actually executed.

Dispatch Groups

If you have multiple tasks, even if added to different queues, and want to wait for their completion, you can group them in a dispatch group.

Let’s see an example, a task can be added to a specific group directly with the sync or async call:

let mygroup = DispatchGroup()

for i in 0..<5 {

globalDefault.async(group: mygroup){

sleep(UInt32(i))

print("Group async on globalDefault:"+String(i))

}

}

The tasks are executed on globalDefault, but we can register an handler for mygroup completion that will execute a closure on the queue we prefer once all of them will be completed. The wait() method can be used to perform a blocking wait.

print("Waiting for completion...")

mygroup.notify(queue: globalDefault) {

print("Notify received, done waiting.")

}

mygroup.wait()

print("Done waiting.")

Another way to do track a task with groups, consists in manually entering and leaving a group instead of specifying it when performing the call on the queue:

for i in 0..<5 {

mygroup.enter()

sleep(UInt32(i))

print("Group sync on MAINQ:"+String(i))

mygroup.leave()

}

Dispatch Work Items

Closures are not the only way to specify a job that needs to be executed by a queue, sometimes you might need a container type able to keep track of its execution status and for that we have DispatchWorkItem. Every method that accepts a closure has a variant for work items.

Work Items encapsulate a closure that is executed by the thread pool of the queue invoking the perform() method:

let workItem = DispatchWorkItem {

print("Done!")

}

workItem.perform()

And WorkItems also provide other useful methods, like notify that as it did with groups allows to perform a closure on a specific queue on completion:

workItem.notify(queue: DispatchQueue.main) {

print("Notify on Main Queue!")

}

defaultQueue.async(execute: workItem)

We can also wait until the closure has been executed or flag it for removal before the queue tries to execute it with the cancel() method (that does not cancel closures during execution).

print("Waiting for work item...")

workItem.wait()

print("Done waiting.")

workItem.cancel()

But it’s important to know that wait() doesn’t just block the current thread waiting for completion but also elevates the priority of all the preceding work items in its queue, to try to complete this specific item as soon as possible.

Dispatch Semaphores

Dispatch Semaphores are locks that can be acquired by more than one thread depending on the current value of a counter.

Threads wait on a semaphore when the counter, decremented every time the semaphore is acquired, reaches 0.

A slot to access the semaphore is released for the waiting threads calling signal that has the effect of incrementing the counter.

Let’s see a simple example:

let sem = DispatchSemaphore(value: 2)

// The semaphore will be held by groups of two pool threads

globalDefault.sync {

DispatchQueue.concurrentPerform(iterations: 10) { (id:Int) in

sem.wait(timeout: DispatchTime.distantFuture)

sleep(1)

print(String(id)+" acquired semaphore.")

sem.signal()

}

}

Dispatch Assertions

Swift 3 introduces a new function to perform assertions on the current execution context, that allows to verify if a closure is being executed on the expected queue. We can build predicates using the three enum cases of DispatchPredicate: .onQueue, to verify that we are on a specific queue, .notOnQueue, to verify the opposite and .onQueueAsBarrier to check if the current closure or work item are acting as a barrier on a queue.

dispatchPrecondition(condition: .notOnQueue(mainQueue))

dispatchPrecondition(condition: .onQueue(queue))

The playgrounds for this and other articles are available from GitHub or Zipped.

Dispatch Sources

Dispatch Sources are a convenient way to handle system-level asynchronous events like kernel signals or system, file and socket related events using event handlers.

There are a few kind of Dispatch Sources available, that can be grouped as follow:

- Timer Dispatch Sources: Used to generate events at a specific point in time or periodic events (DispatchSourceTimer).

- Signal Dispatch Sources: Used to handle UNIX signals (DispatchSourceSignal).

- Memory Dispatch Sources: Used to register for notifications related to the memory usage status (DispatchSourceMemoryPressure).

- Descriptor Dispatch Sources: Used to register for different events related to files and sockets (DispatchSourceFileSystemObject, DispatchSourceRead, DispatchSourceWrite).

- Process dispatch sources: Used to monitor external process for some events related to their execution state (DispatchSourceProcess).

- Mach related dispatch sources: Used to handle events related to the IPC facilities of the Mach kernel (DispatchSourceMachReceive, DispatchSourceMachSend).

And you can also build your own dispatch sources if needed. All dispatch sources conform to the DispatchSourceProtocol protocol that defines the basic operations required to register handlers and modify the activation state of the Dispatch Source.

Let’s see an example with DispatchSourceTimer to understand how to use these objects.

Sources are created with the utility methods provided by DispatchSource, in this snippet we’ll use makeTimerSource, specifying the dispatch queue that we want to use to execute the handler.

Timer Sources don’t have other parameters, so we’ll just need to specify the queue to create a source, as we’ll see, dispatch source able to handle multiple events will usually require that you specify the identifier of the event you want to handle.

let t = DispatchSource.makeTimerSource(queue: DispatchQueue.global())

t.setEventHandler{ print("!") }

t.scheduleOneshot(deadline: .now() + .seconds(5), leeway: .nanoseconds(0))

t.activate()

Once the Source is created, we register an event handler with setEventHandler(closure:) and if no other configurations are required enable the dispatch source with activate() (previous releases of libDispatch used the resume() method for this purpose).

Dispatch Sources are initially inactive, meaning that they will not start delivering events right away allowing further configuration. Once we are ready, the source can be activated with activate() and if needed the event delivery can be temporarily suspended with suspend() and resumed with resume().

Timer Sources require an additional step to configure which kind of timed events the object will deliver. In the example above we are defining a single event that will be delivered 5 seconds after the registration with a strict deadline.

We could have also configured the object to deliver periodic events, like we could have done with the Timer object:

t.scheduleRepeating(deadline: .now(), interval: .seconds(5), leeway: .seconds(1))

When we are done with a dispatch source and we want to just stop completely the delivery of events, we’ll call cancel(), that will stop the event source, call the cancellation handler if we did set one and perform some final cleanup operations like unregistering the handlers.

t.cancel()

The API is still the same for the other dispatch source types, let’s see for example how Kitura initializes the read source it uses to handle asynchronous reads on an established socket:

readerSource = DispatchSource.makeReadSource(fileDescriptor: socket.socketfd,

queue: socketReaderQueue(fd: socket.socketfd))

readerSource.setEventHandler() {

_ = self.handleRead()

}

readerSource.setCancelHandler(handler: self.handleCancel)

readerSource.resume()

The function handleRead() will be called on a dedicated queue when new bytes will be available in the socket’s incoming data buffer. Kitura also uses a WriteSource to perform buffered writes, using the dispatch source events to efficiently pace the writes, writing new bytes as soon as the socket channel is ready to send them. When doing I/O, read/write dispatch sources can be a good high level alternative to other lower level APIs you’ll normally use on *nix platforms.

And on the topic of dispatch sources related to files, another one that could be useful in some use cases is DispatchSourceFileSystemObject, that allows to listen to changes to a specific file, from its name down to changes to its attributes. With this dispatch source you’ll be also able to receive notifications if a file has been modified or deleted, essentially a subset of the events that on Linux are managed by the inotify kernel subsystem.

The remaining source types operate similarly, you can check out the complete list of what’s available in libDispatch’s documentation but remember that some of them like the Mach sources and the memory pressure source will work only on Darwin platforms.

Operations and OperationQueues

Let’s talk briefly of Operation Queues, and additional API built on top of GCD, that uses concurrent queues and models tasks as Operations, that are easy to cancel and that can have their execution depend on other operations completion.

Operations can have a priority, which defines the order of execution, and are added to OperationQueues that be executed asynchronously.

Let’s see a basic example:

var queue = OperationQueue()

queue.name = "My Custom Queue"

queue.maxConcurrentOperationCount = 2

var mainqueue = OperationQueue.main //Refers to the queue of the main thread

queue.addOperation{

print("Op1")

}

queue.addOperation{

print("Op2")

}

We can also create a Block Operation object and configure it before adding it to the queue and if needed we can also add more than one closure to this kind of operations.

Note that NSInvocationOperation, that creates an operation with target+selector, is not available in Swift.

var op3 = BlockOperation(block: {

print("Op3")

})

op3.queuePriority = .veryHigh

op3.completionBlock = {

if op3.isCancelled {

print("Someone cancelled me.")

}

print("Completed Op3")

}

var op4 = BlockOperation {

print("Op4 always after Op3")

OperationQueue.main.addOperation{

print("I'm on main queue!")

}

}

Operations can have a priority and a secondary completion closure that will be run once the main closure completes.

We can add a dependency from op4 to op3, so that op4 will wait for the completion of op3 to execute.

op4.addDependency(op3)

queue.addOperation(op4) // op3 will complete before op4, always

queue.addOperation(op3)

Dependencies can also be removed with removeDependency(operation:) and are stored in a publicly accessible dependencies array.

The current state of an operation can be examined using specific properties:

op3.isReady //Ready for execution?

op3.isExecuting //Executing now?

op3.isFinished //Finished naturally or cancelled?

op3.isCancelled //Manually cancelled?

You can cancel all the operations present in a queue calling the cancelAllOperations method, that sets the isCancelled flag on the operations remaining in the queue. A single operation can be canceled invoking its cancel method:

queue.cancelAllOperations()

op3.cancel()

It’s recommended to check the isCancelled property inside your operation to skip execution if the operation was cancelled after it was scheduled to run by the queue.

And finally, you can also stop the execution of new operations on an operation queue (the currently running operation will not be affected):

queue.isSuspended = true

The playgrounds for this and other articles are available from GitHub or Zipped.

Closing Thoughts

This article should have given you a good summary of what is possible today from the point of view of concurrency using the external frameworks that are available from Swift.

Part 2 will focus on what could come next, in term of language facilities that could handle concurrency “natively”, without resorting to external libraries. A few interesting paradigms will be described with the help of a few open source implementations already available today.

I hope that these two articles will be a good introduction to the world of concurrency and that they will help you understand and participate to the discussions that will take place on the swift-evolution mailing list when the community will start considering what to introduce in, let’s hope, Swift 5.

For more interesting content on concurrency and Swift, check out the Cocoa With Love blog.

Did you like this article? Let me know on Twitter!